Remember being a freshman in high school, and the seniors didn’t give you the time of day? At best, you were getting snubbed and, at worst, you were getting thrown in a trash can or something.

Travonn Johnson was a senior when I was a freshman. He was just the nicest person. He played all the sports and was an amazing athlete. We both ran track, and I remember how incredibly encouraging he was. You could come in last place and he would just wait there for you to give you a clap on the back and cheer you on.

One day, he was driving home with his cousin and two friends in a little VW bug. They had some kind of car trouble and pulled off to the side of the freeway. A drunk driver slammed into them and killed all four of them.

I was struck by the injustice of it, that you could just have your life snubbed out because of someone else’s carelessness. It was the beginning of my sophomore year, and I had just started driving. There were several programs that addressed drunk driving at my high school in Sacramento that were just getting off the ground. I was really drawn to the programs that were student-led, and that focused on circumstances and conditions that led to drunk driving.

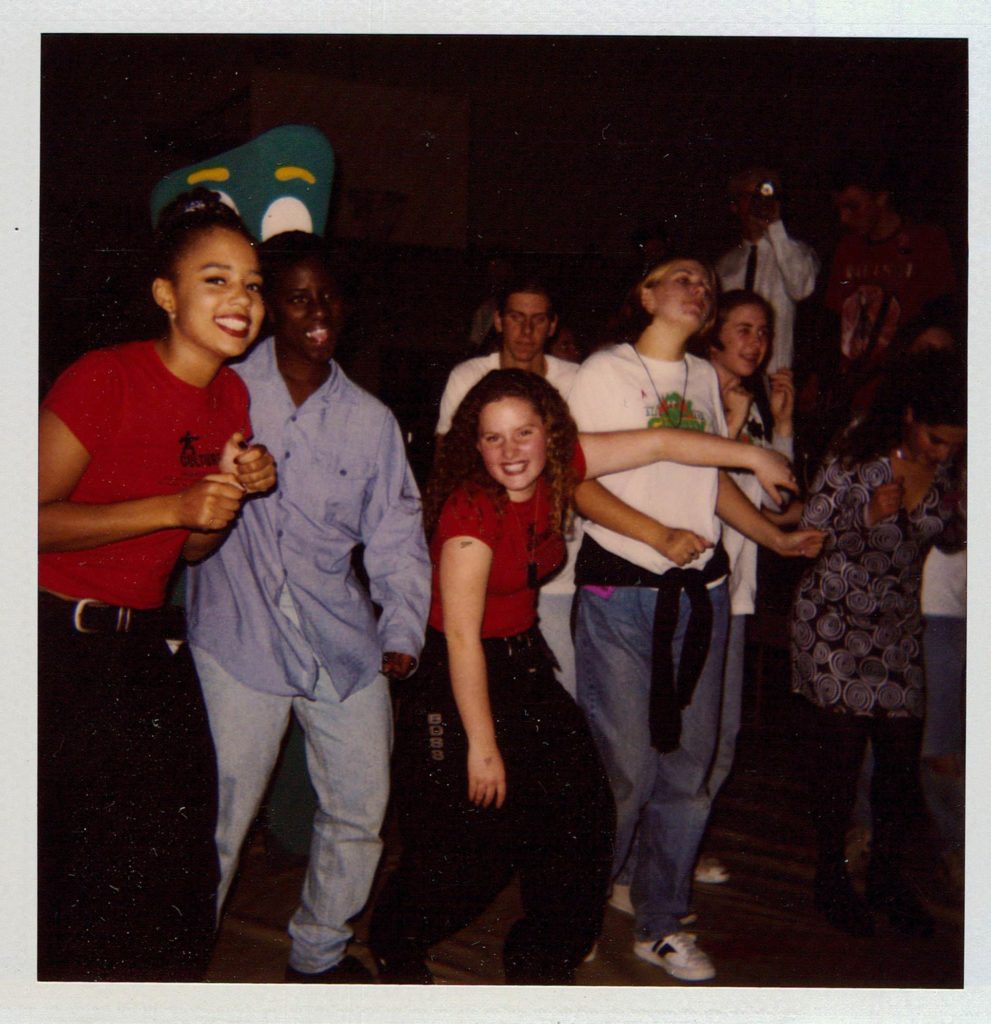

These weren’t just some fun programs to keep kids distracted from drinking. For a lot of us, especially in the communities that were most impacted, it was about how to change the circumstances of our lives, because what we were given was not acceptable. Through Students Reaching Out, for example, we went into elementary and middle schools to talk to younger kids about the choices that they were making. In order to do that work, you had to be a role model yourself. You had to commit to being the person that you were asking these younger people to be, and you had this cohort of peers who were making the same commitment. Doing it together kept members from feeling isolated, and created a positive culture around it that recognized you as a leader. You didn’t have to wait until you were grown. At 14-16 years old, we were learning that we could have a profound impact on younger people.

That was the real power of this youth development movement: letting young people know that we had tremendous power and helping us figure out how to use it. I feel incredibly fortunate that those stars aligned when they did, because I don’t know what the impact would have been on me if I didn’t have a place to focus my leadership. It was an opportunity to channel all of that sadness, all of that rage that I had, into something that was positive.

I started at yli in 1994, fresh out of college. I managed the Marin Youth Commission, the Marin Youth Grants Board, and Youth Leadership San Francisco, which brought students together from different schools across San Francisco to learn about issues impacting the city and build leadership skills. Key among these issues was how certain neighborhoods were being targeted by the tobacco and alcohol industries. I took a handful of the students for a walk around the Fillmore district to take photos of what they saw. There were liquor stores on every corner, and they took photos of the kinds of products that were being sold, and how they were priced. Then, we visited a neighborhood just 9 blocks away. They were able to see that, in the nice neighborhoods, stores sold nice bottles of wine, flowers, and lovely gourmet food. The impact of environmental influences was really clear.

This was equity work before we were calling it equity work. What does it mean for different neighborhoods to be targeted, and what do we need to do about that? What are the kinds of policies and ordinances that we need to put in place? How do we change our language in order to speak to decision makers, that it isn’t about the kids and their bad decision making? My own understanding about the decisions that impact our lives really evolved during this period.

We had youth in the program from different schools all over the city. I had one youth who wouldn’t let me drive him up to his house. He’d make me drop him off up the block because it wasn’t safe to drive into his cul-de-sac. And then I had youth who were living in big, beautiful houses on the beach. So there was a really interesting mix of experiences – they got to learn from each other and witness each other’s worlds.

There were several young people who I got incredibly close to. They would come to the yli office and we’d do all kinds of things. We went to marches and protests. We’d make banners, videos, PSAs. It was about the relationships – we became like family. It wasn’t transactional, it was transformational. I spent so much time with them that I really got to see them and appreciate them. I was able to help them cultivate whatever versions of themselves they wanted to grow into. I’m still in touch with some of these youth today. These kinds of rich relationships are at the heart of youth development work.

I think that there’s something very grounding about maintaining relationships with young people. It keeps me motivated and inspired. Growing up in the youth development movement, I learned to recognize when harm is being done and to object, to stand up to it without feeling like I have to barter or compromise. To say, “we don’t owe you our lives and we’re going to do whatever it takes to reclaim our lives.” Unfortunately, as we get older, we become bureaucrats and lose our passion for the work. For example, I started working 20 years ago working on an ordinance to ban youth from buying tobacco products, and I was shocked by the reaction I got from the youth tobacco control and public health organizations that I thought for sure would be behind it. I couldn’t understand it.

Over time, I learned that they had too much to lose, that they were beholden to Big Tobacco to fund their programs. It was mind blowing to me. I had thought that the point was to work ourselves out of this job, so that we could do something else that our hearts call us to do, and because we didn’t want the next generation to have to do this.

I am really proud that I helped pull this work together. Brookline, Massachusetts, just passed the ordinance, and New Zealand is taking it up. There is a team of attorneys, advocacy groups, professors from all over the world who are working on it, and I’m looking forward to seeing it snowball.

I now run a very bustling consulting firm, the Equity and Wellness Institute, which is an outgrowth of the consulting work I’ve done since I left yli 26 years ago. I was 24 years old and had just found out that I was pregnant. I was scared to death. But my mother took me under her wing to show me the ropes of consulting. She felt that I should always know how to make money for myself, that I should never be beholden to someone else. She was in the Black Panther Party in college. She tells me that she spent more time in the Civil Rights Movement protests and in jail than she did in school when she was a high school sophomore. So I grew up in this household that was all about fighting for our freedom – we never took it for granted. My mom worked in government until she got too frustrated with it, and then started a nonprofit that has become a global organization. I’m really grateful that I had her as my role model.

So many of the things that I do on a day to day basis, emanate from what I learned when I was a teenager in those youth programs. I had to learn how to be comfortable in front of people, because so much of the program was about putting yourself out there. You’re so awkward as a teenager, so self conscious, and we had to learn how to push through that. How many adults never experience that? They’re absolutely terrified when they have to get up in front of people and do anything. We had to plan things, create timelines and budgets, coordinate with other people. We had to figure out how to build on the strengths of the team and make things fun and exciting and attractive so that folks would want to participate. We had to think about how we were going to demonstrate our impact, how we were going to evaluate what we were doing so that participants would want to continue being involved and funders would keep funding us. All of those skills I gained as a teenager I now use in my business.

My mom has come out to talk to my team about her journey – about why this work is so important and that centering freedom is ultimately what the work is about. How do we get to live the lives that we were born to live? We work with a lot of government institutions, holding up a mirror so that they can see the impediments they are creating for communities, especially communities of color. I’m always learning. No two days look the same. I’m always stretching and growing, and I love it. There are so many different ways in which we need to push the bounds, because isn’t this what we all want? To do more than just survive, but to live safe and healthy, blissful lives?